The essential takeaway: Artificial Intelligence officially began in 1956 at the Dartmouth Summer Project, where the term was coined to distinguish it from cybernetics. This founding date matters because it frames today’s powerful generative models not as sudden magic, but as the result of a nearly 70-year evolution that started with a simple summer workshop.

Have you ever found yourself asking exactly when was ai invented, assuming it must be a recent creation born from modern silicon valleys? The reality is far more surprising, as the official birth of artificial intelligence dates back to a bold summer workshop in 1956 where a few visionaries dared to dream of thinking machines. We will explore this defining moment and the rollercoaster history that followed, taking you from those early symbolic logic tests straight to the powerful neural networks that currently define our digital lives.

The Year AI Got Its Name and a Mission

You are likely here because you want a straight answer to the question: when was ai invented? You don’t need a history of ancient philosophy right now. The official birthdate of Artificial Intelligence as a scientific discipline is 1956, and it happened at a specific event in Hanover, New Hampshire.

1956: The Dartmouth Summer Project

If you want the official birth certificate, look no further than 1956, the year everything changed. That summer, a pivotal workshop took place at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. It wasn’t a massive gala, just a focused summer research project.

This is exactly where the term “Artificial Intelligence” was actually invented. John McCarthy chose it specifically to avoid confusion with “cybernetics,” which was the trendy buzzword back then.

Four heavy hitters organized this: John McCarthy (the name guy), Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon. They gathered the brightest minds for a two-month brainstorming session. It was basically the “Constitutional Convention” for smart machines.

The Bold Proposal That Started It All

The proposal was audacious, resting on the conjecture that “every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.”

Talk about overconfidence. They genuinely believed a small group of scientists could make a significant dent in these problems during just one summer.

They weren’t thinking small, listing topics like creativity, natural language processing, and neural networks. It’s wild to realize the major themes of modern AI were already on the table. They mapped out the territory we are still exploring today.

Who Was There: The Founding Fathers

While many came to talk, Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon came to show off. They arrived with something the others didn’t have: a working program called the Logic Theorist. It was the moment the room stopped just theorizing.

The Logic Theorist was capable of proving mathematical theorems from Principia Mathematica. Because it mimicked human reasoning to solve problems, it is widely considered the first true AI program.

Their demo shifted the entire vibe from abstract philosophy to practical engineering. They proved that intelligent machines weren’t just science fiction anymore. It was real, and it was running on a computer.

Why Dartmouth Was a Starting Line, Not a Finish Line

To be fair, Dartmouth didn’t “invent” the concept from absolute zero. Instead, the event formalized and christened a field of research that had been bubbling up in scattered papers. It gave the discipline its identity.

Think of it this way: it was the moment a bunch of solo musicians decided to form an orchestra and finally name the band.

Most importantly, the conference triggered a massive wave of funding and enthusiasm. It provided a roadmap and a unified label for a nascent scientific community. Without this meeting, we might still be calling it “complex information processing.”

The Intellectual Ghosts That Haunted Dartmouth

But long before the name ‘AI’ existed, the ideas were already sprouting in the minds of outliers. The participants of Dartmouth did not start from a blank page; they leaned heavily on the shoulders of a few giants who dared to ask if metal could think.

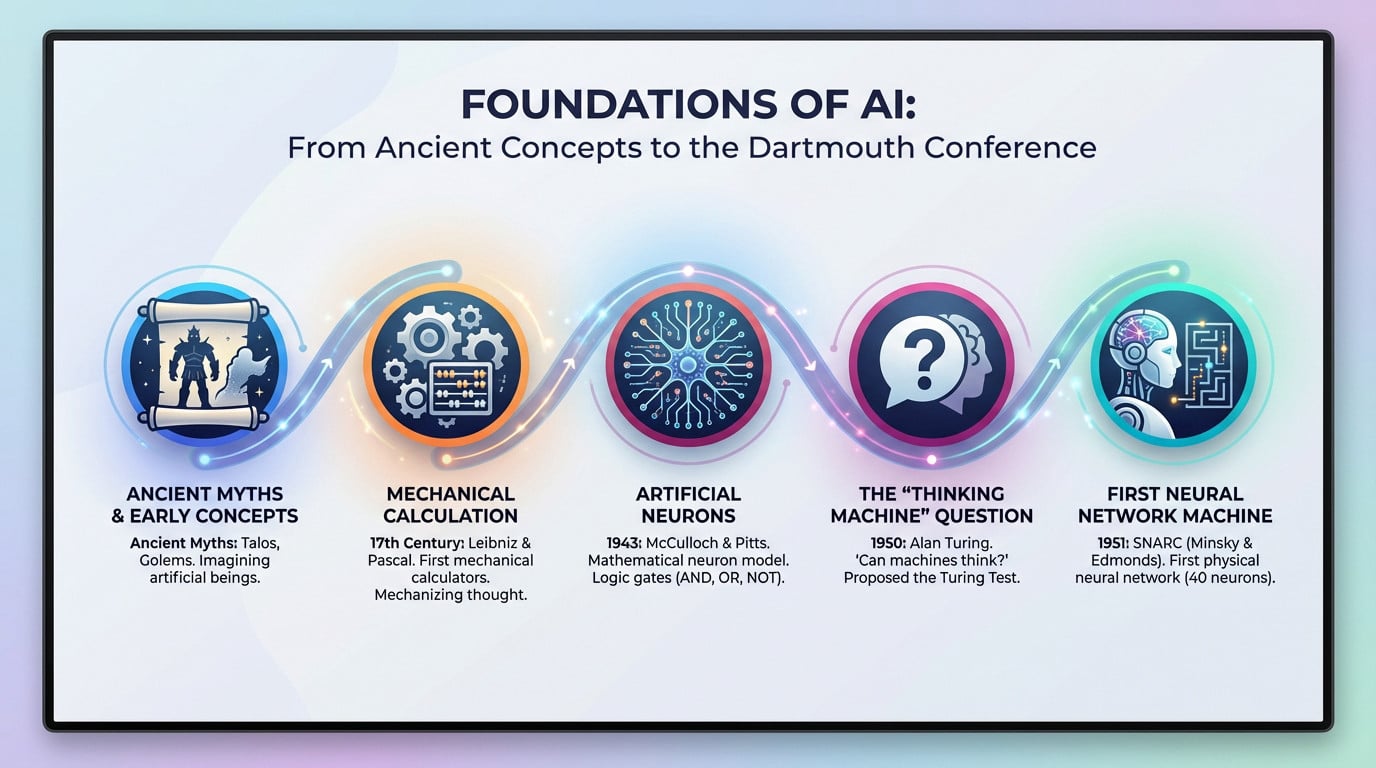

Alan Turing and the “Thinking Machine” Question

You can’t talk about AI without bowing to Alan Turing, the true prophet of this era. In 1950, he dropped a bombshell article titled “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”. It basically predicted the entire industry before it even started.

He asked a simple, terrifying question: “Can machines think?” To avoid getting stuck in endless philosophical debates about the soul, he proposed a practical test instead.

We call it the Turing Test, or the Imitation Game. A machine succeeds if a human cannot determine if they are speaking to a machine or another human. It was a pragmatic way to define intelligence.

The First Artificial Neurons: McCulloch and Pitts

Let’s rewind even further to 1943. Warren McCulloch, a neuroscientist, teamed up with Walter Pitts, a logician. Their work is the absolute bedrock of the entire “connectionist” current of AI.

They created a mathematical model of a biological neuron. They showed that networks of these “artificial neurons” could perform basic logical functions like AND, OR, and NOT. It was the first time logic met biology.

This was the very first time anyone made a formal link between the biology of the brain and the logic of calculation.

From Ancient Myths to Calculating Machines

People often ask when was ai invented, looking for one specific date on a calendar. We must acknowledge ancient Greek myths of automatons like Talos or the Golems first.

But let’s be clear: those myths were stories, not science. The real conceptual work started with philosophers like Leibniz and Pascal who built the first mechanical calculating machines. They turned abstract math into physical gears.

These machines proved that a “mental” process like calculation could be mechanized. This is a fundamental conceptual step required to imagine artificial intelligence. It shifted our perspective on what machines could actually do.

SNARC: The First Neural Network Machine

Then came the SNARC (Stochastic Neural Analog Reinforcement Calculator), built in 1951. It stands as the first physical machine ever constructed to simulate a neural network. It was hardware, not just theory.

Marvin Minsky and Dean Edmonds built it while they were still students. The SNARC simulated a rat learning to exit a maze, using 40 connected “neurons”. It was a messy, brilliant experiment.

It was a proof of concept. We could move from the theory of artificial neurons to a real machine that learns.

The Golden Years: An Age of Unbridled Optimism (1956-1974)

If you dig into when was ai invented, the timeline solidifies here. The Dartmouth kickoff released crazy energy. For nearly twenty years, AI researchers, armed with funding and bulletproof confidence, believed anything was possible.

Solving Problems Like a Human… or So They Thought

Early pioneers bet the house on symbolic reasoning. They assumed human thought was just manipulating symbols, like algebra for the mind. It seemed logical at the time.

Take the General Problem Solver (GPS) by Newell and Simon. They designed this beast to crack absolutely any formal problem.

The method was crude: it explored every possible solution via “brute force search”. This worked fine for simple logic puzzles like the Towers of Hanoi. But for messy real-world issues? It hit a brick wall immediately.

ELIZA: The Chatbot That Fooled People

Then came ELIZA, coded by Joseph Weizenbaum in 1966. It was one of the first stabs at natural language processing, basically a chatbot before the term existed.

ELIZA mimicked a Rogerian psychotherapist. It understood zero context, relying entirely on keyword recognition tricks to rephrase your own words. If you typed “mother”, it just spat back a pre-canned question about your family to keep you talking.

Yet, users fell for it. We call this the “ELIZA effect”—people bonded emotionally with a script they knew was fake.

Microworlds: Building Intelligence in a Box

Real life is chaotic, so researchers retreated into “microworlds”. These were simplified virtual environments where the rules were strict and variables limited. It was much safer to build intelligence there.

Terry Winograd’s SHRDLU (1972) is the classic example here. It featured a virtual robot arm manipulating shapes in a “blocks world”. You could tell it to move a green cone, and it actually understood the physics.

It was impressive because SHRDLU handled complex natural language commands. “Put the blue pyramid on the block” actually worked. It felt like a massive integration of vision and logic.

The Looming Problem of Scale

But a monster was waiting: the combinatorial explosion. The symbolic methods of the era simply didn’t scale up. What worked in a lab failed miserably outside.

Solving a 10-piece puzzle is trivial. But try that with a million pieces, and the number of possible combinations becomes astronomical instantly.

Success in “microworlds” proved to be a mirage. Big promises made to funders like DARPA started ringing hollow. The cash flow stopped, setting the stage for a brutal reality check that would freeze progress for years.

The First AI Winter: When the Money Ran Out (1974-1980)

After the party, the hangover. The initial optimism smashed against the wall of reality, and the funders started turning off the taps.

The Lighthill Report: A Damning Verdict

In 1973, the British government commissioned the Lighthill Report to see if their investment was actually going anywhere. It was supposed to be a routine check-up, but it turned into an autopsy of the current state of research.

Sir James Lighthill didn’t mince words. He claimed AI had failed to keep a single one of its grand promises, reducing the field’s “successes” to mere laboratory toys that couldn’t handle real-world problems. He savagely criticized the complete failure to scale up.

The fallout was brutal and immediate. The UK government slashed budgets for AI research, effectively killing the discipline in the country.

DARPA Gets Impatient in the US

Across the Atlantic, the DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) was the primary wallet behind American innovation. But they weren’t running a charity; they had very specific, concrete expectations for their dollars.

Patience wore thin. The agency grew tired of funding open-ended academic projects that offered no clear military application or practical utility in the near future.

Carnegie Mellon found out the hard way when their speech recognition program funding got axed. DARPA pulled the plug, redirecting millions toward specific targets like battle management systems, leaving many general AI labs starving for resources.

The Curse of Computational Complexity

Here is the technical killer: the “combinatorial explosion.” Early AI programs were mathematically intractable. This means that adding just a tiny bit more data to a problem didn’t just double the work; it required an exponential increase in processing power.

The pioneers had hit a fundamental wall. Their brilliant ideas were simply too demanding for the computers of the 1970s, which had less power than a modern calculator.

The hardware simply wasn’t ready for the ambition. The algorithms were too hungry, and the computers were too slow and expensive. It was a technological dead end.

A Field in Disarray

The mood turned toxic. ““Artificial Intelligence” became a taboo phrase in academic corridors. If you wanted to secure a grant, you didn’t use the name; it was a one-way ticket to rejection.

To survive, researchers rebranded their life’s work. Suddenly, they were experts in “machine learning,” “pattern recognition,” or “knowledge-based systems.” It was a necessary camouflage to keep the lights on.

Yet, this harsh winter forced a cleanup. It pushed the field… to become more rigorous, mathematical, and less dependent on sci-fi storytelling.

The 80s Boom: AI Puts on a Business Suit

Enter the Expert Systems

Let’s talk about Expert Systems. Unlike the broad, sci-fi dreams of the 50s, these programs were designed to mimic the specific decision-making capabilities of a human specialist in one very narrow lane.

Here is the shift: instead of trying to solve every problem under the sun, they focused intensely on a single, well-defined task. They didn’t think broadly; they executed narrowly.

Under the hood, the architecture relied on two pillars: a knowledge base filled with thousands of “if-then” rules coded by humans, and an inference engine, a program that applied those rules to data to reach a logical conclusion.

From the Lab to the Factory Floor

Real-world application finally kicked in. We saw MYCIN diagnosing blood infections with impressive accuracy, and XCON configuring complex computer orders for Digital Equipment Corporation without breaking a sweat.

Money started talking. XCON reportedly saved DEC millions of dollars annually by reducing configuration errors. Suddenly, AI wasn’t just a science experiment; it was a serious, profit-generating business asset.

This success triggered a massive investment wave. Specialized hardware companies like Symbolics and Lisp Machines popped up, selling expensive workstations just to run this specific type of code.

A Tale of Two AIs: A Comparison

To understand the shift, look at how the paradigm evolved. If you ask when was ai invented, the answer changes depending on the method used.

| Feature | Symbolic AI (Golden Era) | Expert Systems (80s Boom) | Connectionism (Modern Era) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Idea | Intelligence as symbol manipulation. | Capture and replicate human expert knowledge. | Intelligence emerges from simple, interconnected units (neurons). |

| Method | Logic, rules, and search algorithms (e.g., GPS). | Hand-crafted “IF-THEN” rule bases. | Learning from data (training neural networks). |

| Key Strength | Good for well-defined, logical problems (puzzles, games). | High performance in a very narrow domain. | Excellent for pattern recognition (images, sound, text). |

| Key Weakness | Brittle, fails with uncertainty, doesn’t scale. | Knowledge acquisition is a bottleneck; cannot learn. | “Black box” nature, requires massive amounts of data. |

The Brittleness of Hand-Coded Knowledge

But there was a massive catch: brittleness. These systems were incredibly fragile. If they encountered a situation even slightly outside their pre-programmed rules, they didn’t just guess; they failed completely.

Think of a cook who can only follow a recipe. If one ingredient is missing, they freeze. They can’t improvise, and neither could these rigid systems.

This created the “knowledge acquisition bottleneck.” The process of sitting down with experts, extracting their intuition, and translating it into code was excruciatingly slow and expensive, which ultimately limited how much these systems could actually scale.

The Second Freeze and the Silent Comeback of Neural Nets

The euphoria surrounding expert systems didn’t last forever. The market eventually collapsed, but while the world of symbolic AI was shivering in the cold, another approach—older and more resilient—was warming up backstage.

The Collapse of the Lisp Machine Market

To understand the crash, you have to look at the hardware. Lisp machines were the heavy lifters of the era—specialized, incredibly expensive computers designed exclusively to run AI programs written in Lisp.

What triggered their extinction around 1987? It was simple economics. General-purpose PCs and office workstations from Apple and IBM became powerful enough to handle the workload, making those pricey, specialized machines totally obsolete.

The market for expert systems was tied to that hardware. When the machines died, the software market crashed, triggering the second AI winter.

Why the Hype Died Down Again

Why did the funding freeze over again? It wasn’t just a hardware issue. The industry had made massive promises it couldn’t keep, leading to a widespread feeling of disappointment among investors.

Here is exactly why the bubble burst this time around:

- Maintenance Hell: The rule-bases of expert systems became impossible to update and maintain as they grew larger.

- High Costs, Unclear ROI: Building and deploying an expert system was extremely expensive, and the return on investment was often disappointing.

- Limited Scope: The systems were too narrow. A medical diagnosis AI couldn’t even understand what a “patient” was outside its specific rules.

- Rise of Cheaper Alternatives: Simpler, conventional software solutions often did the job well enough for a fraction of the cost.

The Quiet Return of Connectionism

While the symbolic approach was crashing, a stubborn minority kept working on neural networks. This approach, known as connectionism, was quietly surviving in the background despite the lack of funding.

Then came a massive theoretical shift in the mid-80s: the rediscovery and popularization of the backpropagation algorithm. It was the mathematical key that finally allowed scientists to train deep neural networks effectively.

You can thank figures like Geoffrey Hinton, Yann LeCun, and Yoshua Bengio, who championed this approach when it wasn’t cool.

Paving the Way for the Modern Era

Even though this research happened away from the spotlight, it was foundational. If you’re asking when was ai invented in the way we use it today, this is the real turning point.

We saw concrete results, too. Yann LeCun successfully applied this to handwritten digit recognition, a system that helped banks read checks automatically.

The late 20th century ended with a strange divergence. While commercial AI hype was dead, fundamental machine learning research was silently laying the concrete for the massive AI domination.

The Man vs. Machine Showdowns

Nothing grabs attention like a good fight. If you ask when was AI invented, the academic answer points to 1956, but for the general public, the technology truly arrived much later. At the turn of the century, AI finally stepped out of the theoretical labs to challenge the greatest human champions on their own turf.

1997: Deep Blue Checkmates Kasparov

The world gasped when IBM’s Deep Blue defeated the reigning world chess champion, Garry Kasparov. This wasn’t just a game; it was the historic moment silicon finally outmatched a human grandmaster.

But let’s be honest. This wasn’t “intelligence” in the human sense. It was massive brute force. The machine used custom chips to evaluate a staggering 200 million positions per second, crushing Kasparov with raw calculation.

This victory marked the peak of the symbolic approach. It was a triumph of sheer computing power, effectively the swan song of that specific era of AI development.

The Symbolic Victory and Its Limits

Here is the catch. Many AI insiders weren’t actually impressed. They saw Deep Blue as a magnificent feat of engineering, sure, but not a real breakthrough in true intelligence.

Why the skepticism? Because Deep Blue’s method wasn’t generalizable. An AI built solely to play chess is useless at everything else. It couldn’t even play checkers without being rebuilt.

Yet, the psychological impact was undeniable. To the public, it proved machines could finally surpass humans in a task we considered the absolute pinnacle of intellect.

2016: AlphaGo and the “Divine Move”

Fast forward to the ancient game of Go. It is infinitely more complex than chess. The number of possible board positions exceeds the number of atoms in the universe, making brute force totally useless.

Enter AlphaGo, developed by DeepMind. In a match watched by millions, it crushed Lee Sedol, one of the world’s top players. This was the moment everything changed.

The machine’s infamous “Move 37” was so unexpected, so alien, that commentators first thought it was a mistake. It was a move born not from brute force, but from something resembling intuition.

Why AlphaGo Was Different: A New Kind of Intelligence

This was fundamentally different from Deep Blue. AlphaGo didn’t just calculate; it combined deep learning with reinforcement learning to actually understand the game’s flow.

First, it studied thousands of human games. Then, it played millions of matches against itself, constantly refining its own neural networks to get better.

Here is the real rupture. AlphaGo wasn’t programmed to play Go well. It learned to play. It developed alien strategies that centuries of human study had never even discovered.

The Deep Learning Tsunami: How Data and Power Changed Everything

AlphaGo’s victory was just the tip of the iceberg. Behind the curtain, a massive tidal wave called deep learning was completely reshaping the entire field.

The Old Idea That Finally Found Its Moment

Neural networks are not exactly fresh technology. Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts actually proposed the concept back in 1943. People often ask when was ai invented, not realizing these seeds were planted decades ago, remaining a dusty academic curiosity for the better part of a century.

So, why did they flop for so long? Simple. We lacked the fuel and the engine. Researchers didn’t have enough data to train them, and computers simply lacked the raw power to run them effectively.

Then came the early 21st century shift. Moore’s Law kept boosting processor speeds, while the internet explosion generated oceans of data (Big Data). Suddenly, the math that looked good on paper started making sense in reality.

The Three Ingredients of the Deep Learning Recipe

This success wasn’t magic; it was engineering. The sudden rise of deep learning relies on the convergence of three specific elements. It is the exact recipe that flipped the switch.

The Holy Trinity of Deep Learning:

- Massive Datasets: The internet provided huge, labeled datasets like ImageNet (millions of categorized images), which served as the perfect training material for hungry neural networks that needed examples to learn.

- Parallel Computation (GPUs): Engineers discovered that Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), originally designed for rendering video games, were incredibly efficient at the parallel matrix calculations needed for training neural nets. This discovery was the spark that ignited the explosion.

- Algorithmic Improvements: Refinements to algorithms like backpropagation and new network architectures made it possible to train much deeper (hence “deep” learning) and more complex models without them failing or getting stuck.

2012: AlexNet and the ImageNet Moment

Enter the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC). Think of it as the World Cup for computer vision. Teams competed to see whose software could identify objects with the least amount of embarrassment.

In 2012, the status quo shattered. A deep neural network named AlexNet, built by Geoffrey Hinton’s team, pulverized the competition. Its error rate was nearly half that of the runner-up. It was a massacre.

The shock was instant. Computer vision experts, who were previously skeptical, ditched their old methods and pivoted to deep learning practically overnight.

From Recognizing Cats to Driving Cars

That victory kicked the door wide open. Suddenly, deep learning techniques weren’t just for identifying dog breeds; they were aggressively applied to countless unsolved problems.

Look at your phone. Voice recognition like Siri and Alexa, instant machine translation, and even medical diagnosis from scans all stem from this shift.

But it gets bigger. This same technology is the brain behind self-driving cars, allowing vehicles to “see” pedestrians and interpret the road. AI stopped being a parlor trick and finally entered the real world with serious consequences.

The New Frontier: Generative AI and the LLM Era

Then, everything accelerated. While people often ask when was ai invented to find a single date in the past, the reality is we just stepped into a completely new timeline. AI learned not only to recognize patterns but to create them. We entered the era of generative AI, and honestly, the world will never be the same.

The Transformer Architecture: “Attention Is All You Need”

In 2017, a team at Google released a research paper that quietly shifted the entire technological landscape: “Attention Is All You Need”. This specific document introduced the Transformer architecture, which remains the backbone of modern AI.

Here is the core concept you need to grasp: the attention mechanism. It allows the model to weigh the importance of different words in a sentence, regardless of their distance from each other, to fully understand the context.

Unlike previous attempts, this architecture was highly efficient and parallelizable for processing long text sequences, effectively paving the way for massive language models.

BERT, GPT, and the Rise of Large Language Models

The first real fruits of the Transformer architecture arrived very quickly. We saw the birth of BERT from Google in 2018 and the original GPT from OpenAI that same year.

You have likely heard the term Large Language Model (LLM) thrown around. These are essentially gigantic Transformer models, trained on nearly the entire Internet, designed to predict the next word in a sequence with uncanny accuracy.

Suddenly, ““emergent” capabilities appeared. These models began to summarize, translate, and even reason without being explicitly trained to do so.

2020 and Beyond: When AI Became Mainstream

The true turning point hit with the release of GPT-3 in 2020. Its ability to generate text that sounded almost human stunned the entire technology community and made us rethink what machines could do.

But the real moment of no return for the public was the launch of ChatGPT in late 2022. AI became a daily conversation for everyone.

At the same time, we saw an explosion in image generation models like DALL-E 2 and Midjourney. AI was no longer just textual; it had become visually creative, blurring the lines between art and algorithm.

What Is Generative AI, Really?

So, what is it? Generative AI is simply an AI that creates new content instead of just analyzing or classifying existing data.

- It’s a Synthesizer: It doesn’t “think” or “understand” but excels at pattern matching and synthesizing plausible content based on its training data.

- It’s Probabilistic: Its output is based on probabilities. It generates the most likely sequence of words or pixels, which is why it can sometimes “hallucinate” or make up facts.

- It’s a Culmination: This era is not a new invention from scratch. It’s the direct result of decades of progress: the idea of neural nets, the backpropagation algorithm, massive data, and immense computing power.

From a hopeful summer workshop in Dartmouth to chatbots writing poetry, AI has truly come a long way. It survived two freezing winters to become our era’s defining technology. The ambitious dream of 1956 is finally alive and kicking—even if it still hallucinates the occasional fact.