Key takeaway: Created in 1966 by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT, ELIZA illustrated the ELIZA effect: humans perceive intelligence where there is only simulation. This crucial lesson for the banking and insurance sectors requires absolute transparency about the limits of chatbots, avoiding any confusion about their ability to handle sensitive data or understand complex contexts.

For financial institutions, trust depends on absolute transparency when it comes to AI technologies. The eliza chatbot, the first conversational program created in 1966 at MIT, revealed the ELIZA effect: a human tendency to attribute real intelligence to systems incapable of possessing it. Discover how this landmark study guides the ethical design of banking and insurance chatbots, clearly aligning customer expectations with real capabilities, preventing risks of mistrust and ensuring compliance with strict regulatory standards and professional ethics for a lasting customer relationship.

ELIZA chatbot: the origins of conversational artificial intelligence

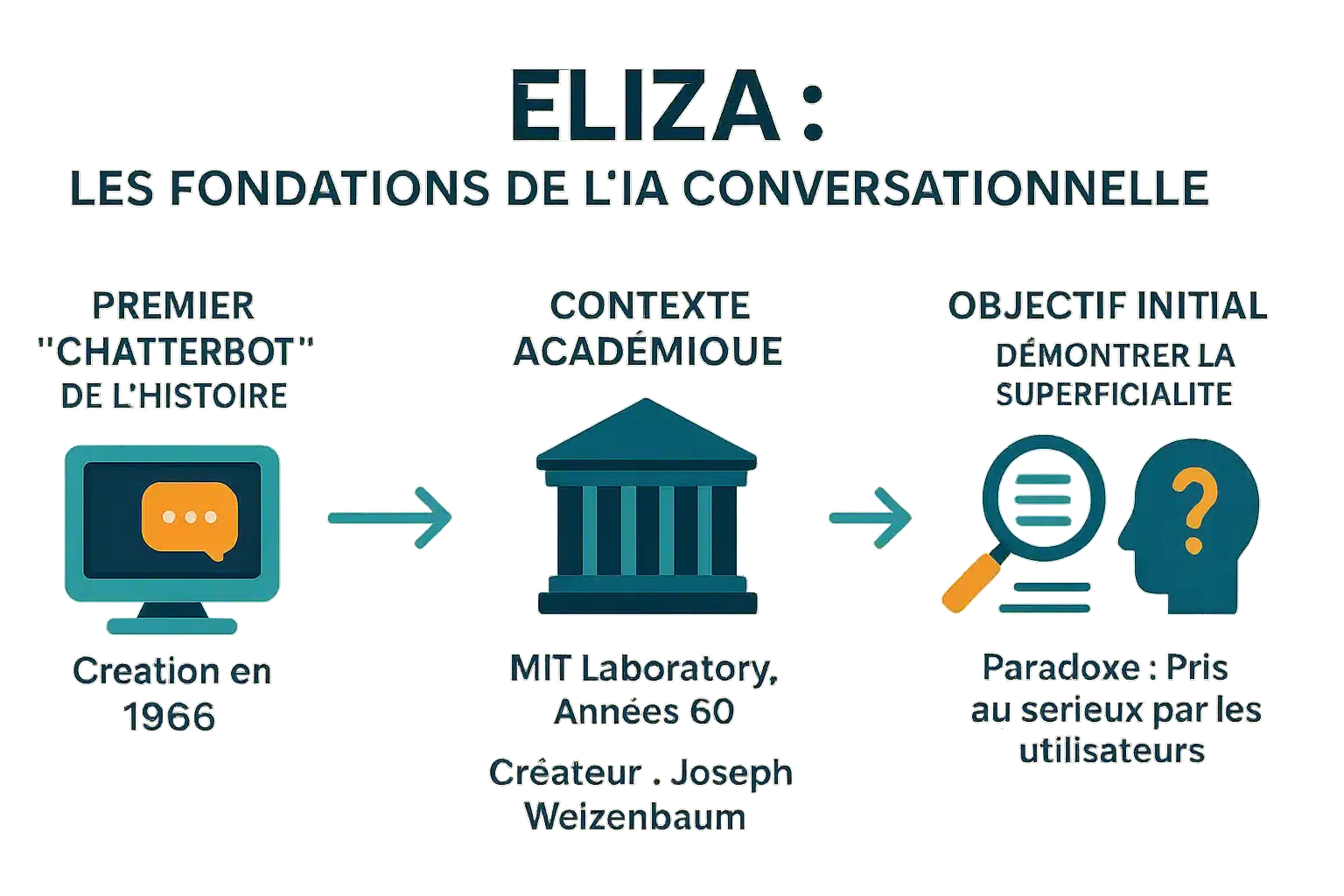

History’s first chatterbot

Created in 1966 by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT, ELIZA is the first chatbot in history. Its name was inspired by Eliza Doolittle (‘Pygmalion’), symbolizing evolution through interaction. It transformed phrases like ‘I’m scared’ into ‘Why are you scared?’ via keyword recognition and substitution. This mechanism, with no real understanding, influenced modern assistants and showed that even simple programs could deceive users.

A creator and a context: MIT in the 1960s

Developed at MIT between 1964-1967, ELIZA used MAD-SLIP and Lisp scripts. The DOCTOR script simulates a Rogerian psychotherapist, rephrasing statements without any external basis. Rediscovered in 2021 after being lost for decades, its source code makes it possible to reconstruct old conversations and study the techniques of the time.

The initial objective: a demonstration of superficiality

Weizenbaum’s aim was to demonstrate the superficiality of human-machine exchanges. He wasn’t looking for real AI, but to reveal how humans project intelligence onto simple machines. Users, including his secretary, shared personal information, believing they were talking to a human. The ELIZA effect, a major psychological phenomenon, underlines this tendency to anthropomorphize. In ‘Computer Power and Human Reason’, he warned against this confusion. ELIZA still inspires modern chatbots. A recent study from 2023 showed that it outperformed GPT-3.5 in a Turing test, but not GPT-4 or humans.

How ELIZA works: an illusion of understanding

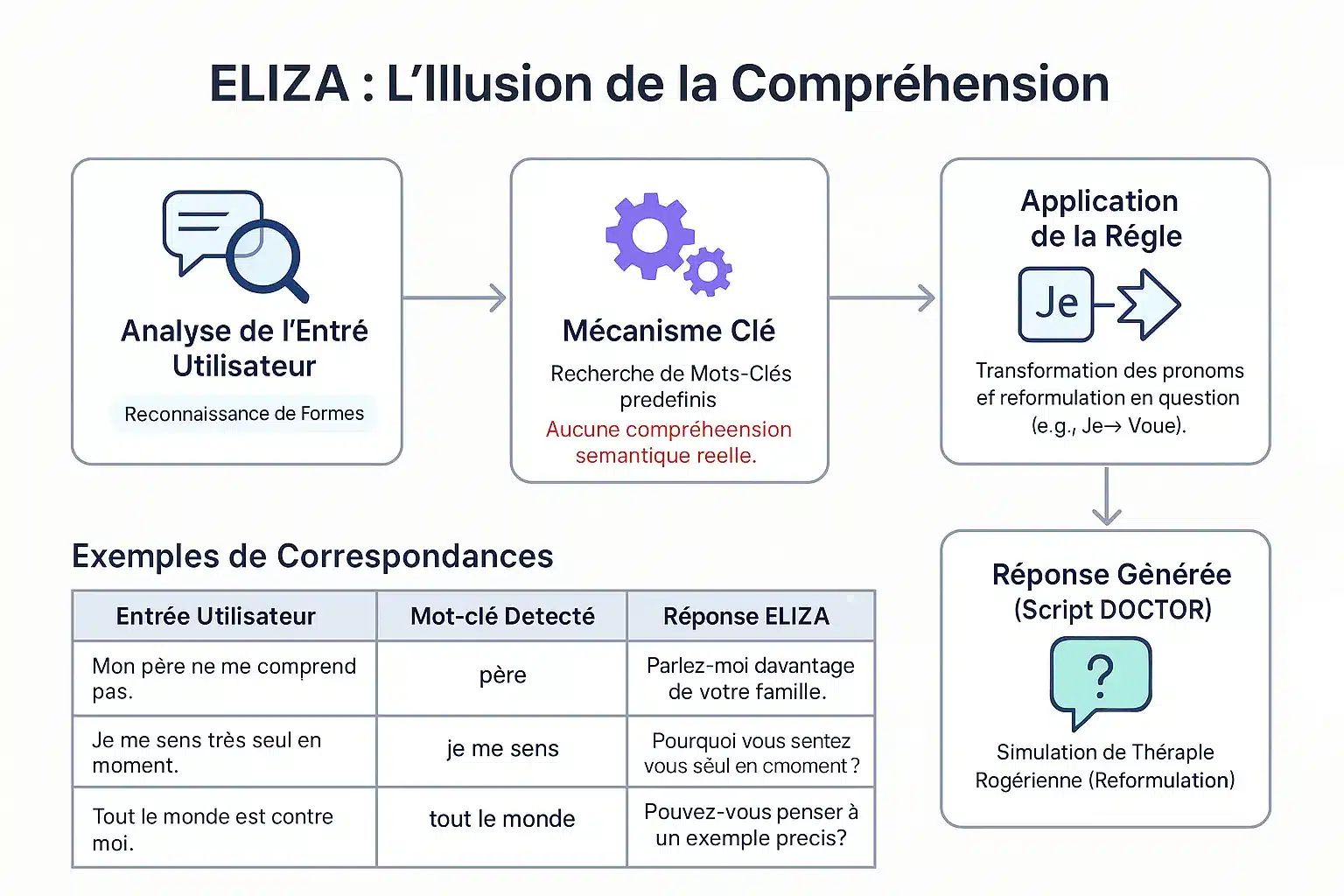

Created in 1966 by Weizenbaum, ELIZA demonstrated the superficiality of man-machine exchanges. Despite its simplicity, it provoked an unexpected reaction: users shared personal details, believing in genuine empathy. This “ELIZA effect” led Weizenbaum to warn of the

The pattern matching method

ELIZA identifies keywords via a keystack. Depending on their priority, it breaks down and reassembles sentences. Example: “I” → “you” to reformulate into questions. “My father doesn’t understand me” → “Talk about your family.” No real understanding: a pattern mechanism simulates empathic listening.

The famous “DOCTOR” script and Rogerian therapy

The DOCTOR script, inspired by Rogerian therapy, reflects the patient’s words without advice. Example: “I feel lonely” → “Why lonely?”. Weizenbaum chose this context to avoid an external basis. This simplicity revealed the human propensity to anthropomorphize machines. ELIZA laid the foundations for modern chatbots. A 2023 study shows that it outperformed GPT-3.5 in a Turing test, but not GPT-4 or humans.

| Input | Keyword | Response |

|---|---|---|

| My father doesn’t understand me. | father | Talk about your family. |

| I feel lonely. | I feel | Why lonely? |

| Everyone is against me. | everyone | Give a specific example. |

| I think I need help. | I think | Do you think you need help? |

The ELIZA effect: when humans project intelligence onto machines

Definition of a major psychological phenomenon

The ELIZA effect refers to the tendency to attribute human understanding to computer-generated symbols. A dispenser displaying “THANK YOU” is perceived as genuine gratitude, even though it has been pre-programmed.

Observed as early as 1966 with ELIZA, Joseph Weizenbaum’s first chatbot at MIT, this phenomenon shows that users projected emotions and understanding onto its simple answers, despite its simplicity. The effect is the result of cognitive dissonance.

Users are aware of the mechanical program, but act as if they understand it. This illusion, after brief interactions, warns of the limits of AI and the risks of overconfidence.

Anthropomorphism and Weizenbaum’s reaction

Joseph Weizenbaum created ELIZA in 1966 to demonstrate the superficiality of man-machine interaction. He was surprised that users developed ”

This reaction prompted him to criticize AI, pointing out that machines lack human judgment. In ‘Computer Power and Human Reason’, he described it as obscene to entrust judgments to machines, particularly in psychology or justice, as only humans bear moral responsibility. His work inspires ethical debate.

The ELIZA effect highlights our propensity to anthropomorphize machines, attributing to them an intelligence and empathy that they don’t possess – a phenomenon that’s still with us today.

The characteristics of this illusion

These manifestations reveal a cognitive dissonance between technical knowledge and user behavior. The main ones are :

- Attribution of consciousness or intentionality even to pre-programmed responses.

- Projecting emotions onto the answers despite their simplicity.

- Sharing personal information without reservation, believing in empathetic listening.

- The feeling of being listened to and understood by a machine.

This illusion is reinforced by interfaces that encourage anthropomorphization (names, dialog). Some people develop emotional attachments, or even fall in love with chatbots, believing in a real relationship. We need to distinguish between weak AI (without conscience) and strong AI. Professionals must promote transparency to avoid abuses.

ELIZA’s legacy: a cornerstone for modern AI

ELIZA, created in 1966 by Joseph Weizenbaum, revealed a flaw in AI perception. Its operation based on keyword recognition illustrated the limits of primitive AI, an essential lesson for financial institutions where the transparency of automated systems protects customers against misinterpretation.

The forerunner of conversational AI

Developed at MIT in 1966, ELIZA simulated a psychotherapist via a DOCTOR script. For example, a sentence like “I’m stressed” was transformed into “Why do you feel stressed?”. Despite its lack of real understanding, it fooled users, creating an illusion of human dialogue.

The ELIZA effect demonstrated the human propensity to anthropomorphize machines, a phenomenon still relevant with modern virtual assistants. This precursor to the Turing test highlighted the challenges of conversational simulation, while inspiring today’s chatbots.

Technical limitations and designer’s warnings

ELIZA lacked contextual memory and understanding of meaning. Its responses depended entirely on predefined rules. In his book Computer Power and Human Reason, Weizenbaum emphasized the fundamental distinction between mechanical calculation and human judgment.

Despite its revolutionary nature, ELIZA was no more than an intelligent mirror of the user’s words, revealing its limitations in the face of complexity and highlighting the gulf between simulation and understanding.

This criticism remains crucial for the bank: in lending or fraud detection, AI must always be supervised by human experts to avoid erroneous decisions and maintain legal accountability.

The resurrection of the original code: archaeological news

In 2021, ELIZA’s source code was found in the MIT archives and published as open source. In 2024, a team restored it on an IBM 7094 emulator, faithfully reproducing the original interactions.

This historical restoration offers a glimpse into the early days of conversational AI. The code, accessible in GNU Emacs, is used in university curricula to teach the fundamentals of AI and received a Legacy Peabody Award in 2021.

For the financial sectors, ELIZA reminds us that AI lacks real understanding. Clear transparency about its capabilities limits the risks of excessive sharing of personal data, and strengthens customer confidence in digital services.

ELIZA today: a fundamental lesson for the AI era

More than an artifact: a timeless case study

ELIZA, created in 1966 by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT, marked a milestone in the history of AI. This chatbot used simple patterns and rules to simulate a conversation. The “DOCTOR” script mimicked a Rogerian psychotherapist, reformulating statements into questions. Yet it didn

Yet users often perceived human understanding. This “ELIZA effect” reveals our tendency to anthropomorphize machines. Today, in the face of LLMs, this distinction between simulation and genuine intelligence is vital. Financial institutions must

Implications for companies and trust management

In the banking and insurance sectors, managing customer expectations is paramount. Chatbots need to be transparent about their nature: they don’t understand language, only simulate responses.

- Clearly define the capabilities and limitations of chatbots for customers.

- Avoid overselling the empathy or understanding of automated agents.

- Take into account the psychological impact of man-machine interactions when designing customer paths.

- Ensuring ethical responsibility in the deployment of simulated technologies.

These principles enable us to build lasting customer relationships based on transparency and trust. In a sector where trust is essential, this vigilance is essential to prevent disappointment and maintain reputation.

ELIZA, despite its age, illustrates the essential point: a simulation is not understanding. For banks and insurance companies,

FAQ

What is the ELIZA effect and what does it mean for financial institutions?

The ELIZA effect refers to the tendency of users to attribute human understanding and intelligence to automated systems, even when they lack these capabilities. In the banking sector, this effect can lead to over-reliance on chatbots, risking misunderstandings about their real limitations. Institutions therefore need to systematically clarify the capabilities and restrictions of these tools in order to preserve the transparency and security of customer interactions.

What was the ELIZA chatbot and its historic role?

Created in 1966 by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT, ELIZA is considered the first chatbot in history. Its operation was based on a pattern matching method that generated responses based on predefined rules. Although initially designed to simulate Rogerian therapy, ELIZA revealed the limits of machine understanding, underlining the importance of transparency in human-machine interaction, a key principle for modern banking services.